Question: Is dry-brining a potato a thing?

You can jump to the recipe.

I haven’t eaten a potato in years because the carbohydrates in them have been inhibitory to my current way of thinking. However, now that my bowels have recovered and my body weight is at a high school level, I thought I would roast a couple of spuds for tea.

In my mind, a potato that is quite moist would benefit from some dehydration before cooking. That’s the theory behind double and triple-cooked chips. I thought I’d halve a couple of spuds, parboil them, season them, and then leave them overnight uncovered on a rack in the refrigerator. What could go wrong?

I asked Microsoft Copilot for an opinion.

To my surprise and delight, the answer was along my way of thinking.

Yes, dry-brining a potato is a thing—it’s just not as common as dry-brining meats, but the principles apply to starchy vegetables, too.

How It Works:

Dry-brining involves liberally applying salt to the surface of food and allowing it to rest before cooking. With potatoes, the salt draws out moisture from the skin and edges. Over time, this moisture mixes with the salt and is reabsorbed, infusing the potato with a deeper, more uniform flavour, which also helps dry out the surface. This drying effect is particularly beneficial when developing crispy roasted potatoes.

Practical Tips according to Microsoft Copilot:

Preparation: Start with a clean, thoroughly dried potato. The drier the surface initially, the more effective the dry brine will be.

Application: Sprinkle salt evenly over the potato.

Rest Time: Let the salted potato sit—ideally uncovered in a cool place or refrigerator—for at least an hour or overnight. This rest period allows flavours to penetrate and moisture to evaporate, which can lead to that sought-after crispy exterior when cooked.

Cooking: Proceed with your usual roasting method.

This method is an application of culinary science. At the same time, it’s used primarily for meats due to its protein interactions; the same basic salt-and-wait technique can work wonders for potatoes by intensifying their natural flavours and improving texture.

Question: What would I eat with the spuds?

In a Microsoft Teams chat with work colleagues, roast lamb was discussed on Friday. In addition, Lorraine from Not Quite Nigella wrote about lamb shoulder for Easter this week. It seemed lamb would be an obvious choice.

Last week, in the same Microsoft Teams group, I mentioned that the only good thing (in my opinion) about the temperature change was that I could put my butter dish out on the bench again. On the days of 43 °C, temperatures were too hot for butter on the bench. A work colleague suggested I invest in a butter bell. I’d never heard of a butter bell, so I was intrigued. I bought one, and hopefully, my butter will remain firm next summer. While I have serious doubts about maintaining firmness >30 °C, the main benefit will be restricting access to pseudomonads, which cause the microbial joy of rancidity. In addition, limiting access to air will minimise oxidative rancidity [here’s an essay on butter rancidity].

Recipe

Ingredients

- Lamb — shoulder (boneless)

- Salt

- Potato — Desiree

- Beef fat

- Rosemary

Equipment

Instructions

- Dry brine the potatoes and the lamb.

- Heat the Weber Q+.

- Insert the meat thermometer.

- Roast the lamb and potatoes until the lamb gets to about 57 °C (135 °F).

- Sear the roast lamb with the gas torch.

- Rest the meat.

- Slice the meat.

- Serve the meat.

- Eat the meat.

Thoughts on the meal.

It’s been a long time since I’ve eaten roast potatoes. These potatoes were delicious. The outside was crispy, the inside was pillowy and soft, and the seasoning was on point.

The lamb was medium rare and tender. I am feeling full.

Photographs

This is a gallery of photographs. Click on one and scroll through the rest.

My beach walk this morning was a bit dreary at sunrise.

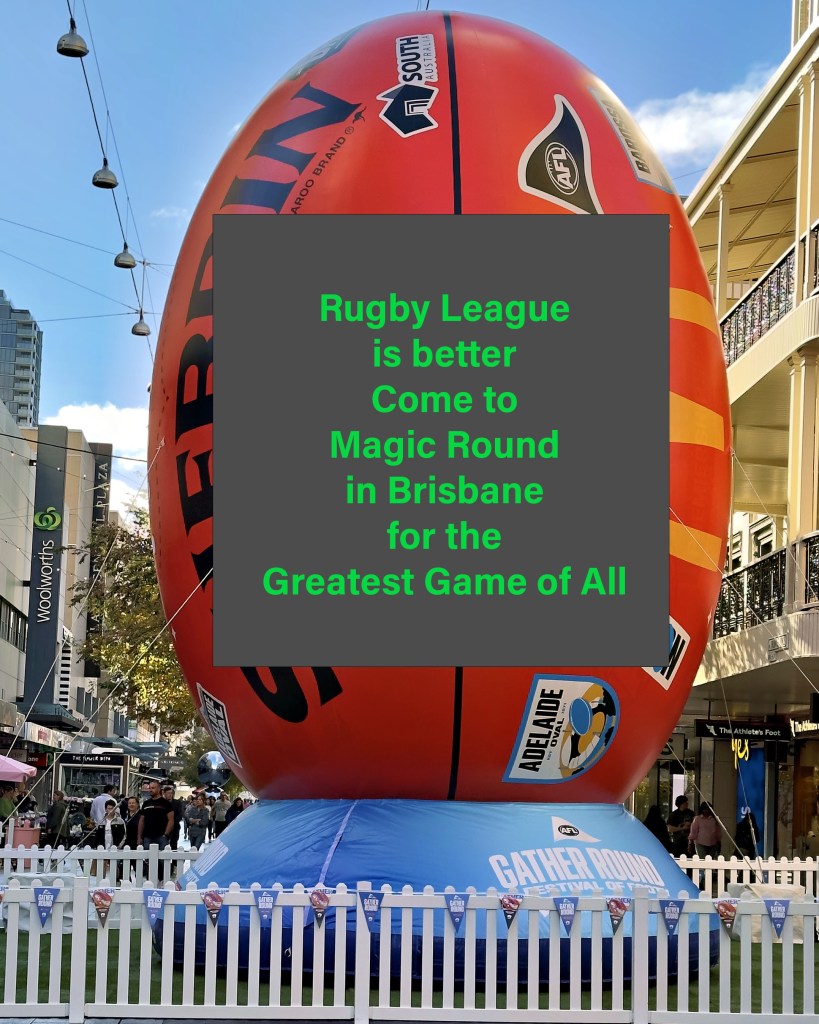

Later in the day, I walked through the mall, and there was this dirty big Aussie Rules ball in the middle. I’ve expressed my protest on social media.

Leave a reply to ckennedy Cancel reply